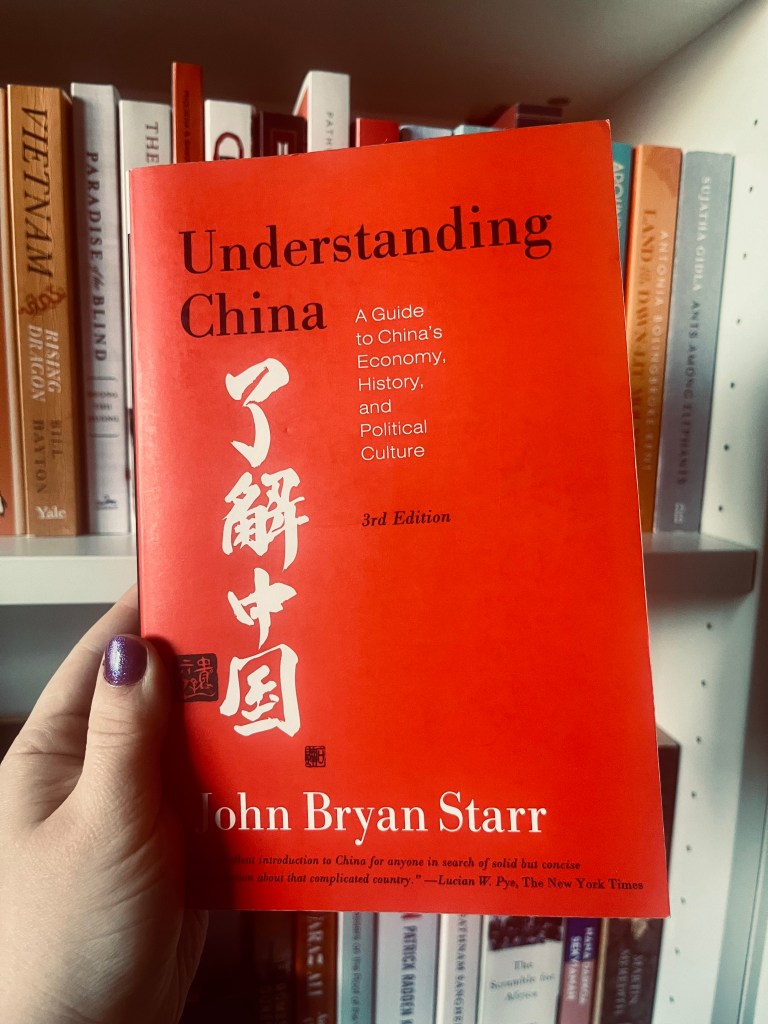

Author: John Bryan Starr

Rating: ⭐️⭐️⭐️⭐️⭐️

I don’t need to point out the importance of China in the world today. It’s the second most populous country in the world, one of the richest (by overall GDP), arguably the most influential in East Asia and one of the most instrumental in the rest of the world, including a number emerging economies in the global south. It’s also where everything seems to be made nowadays as well as the largest consumer market in the world, and this economic power along with its current political climate is something of which every political force in the West is conscious.

If you want to understand some of the history and context of why China is the way it is today and better understand current events concerning it, I can’t recommend this book highly enough. It covers a broad range of subjects from history to politics to the economy. It gives insight into life in cities and rural parts of China, an understanding of China’s attitude towards the environment as well as ethnic minorities and special administrative regions.

This book made me think a lot about the interconnectedness of economics, culture and the environment. I feel like we often compartmentalise these things and target policy at one or another, but the reality is that they play off each other so frequently.

Take China’s famous one-child policy. This was born out of astronomical population growth that for many years had China leading the world in population numbers with over 1.4 billion people (it was just recently surpassed by India). This is both one of their greatest assets and their greatest concerns. It’s an asset because they’ve got a very large consumer base, which means that in a global economy, those that make stuff (companies, countries, people) are eager to access the Chinese market, and the government maintains power by being the gatekeeper of that access. Additionally, a large population means an ample number of people to contribute to the economy in both low-skilled manufacturing jobs, which China has become known for, as well as high-skilled technical jobs, which has been a more recent development in China’s economic growth.

On the other hand, 1.4 billion people is 1.4 billion mouths to feed and bodies to house and people who will at some point in their lives need medical treatment and so on. The government acknowledged that growth at the rate they were going was unsustainable, so implemented the one-child policy where (as it says on the can) couples may only have one child (with some exceptions).

This feels like it should be a no-brainer. Your problem is too many people, so you stop producing as many people. But even taking away the highly predicable enforcement issue (reproduction is both highly personal and no one likes being told how to do it, so how do you punish those who violate the policy or prevent them from doing so without terrible human rights violations?) and the future issues of supporting a large aging population with a smaller pool of people of working age, there’s also the knock-on effects when parents are forced into a corner.

As you may know, the one-child policy in China has manifested in parents choosing to have boys over girls when they can. This is because, as in many Asian cultures, it is the boy’s responsibility to care for his parents in old age, while the girl will presumably get married and care for her husband’s parents. This happened through gender-selective abortions, giving baby girls up for adoption or, in the worst cases, infanticide.

I remember when learning about this as a teenage girl, I was extremely judgemental of the Chinese parents for these decisions, but I now understand they didn’t have much of a choice. There is no universal social security support in China. After the collapse of the state sector of the economy, in which citizens working for state enterprises were provided cheap or free housing, healthcare, and childcare along with pensions and lifetime job security, many urban workers no longer have access to state pensions and social security as a system is fairly new and may not even be available to rural workers at all. So of course Chinese parents, if given a choice would choose a boy, as this was, for many of them, their only option in terms of a retirement plan. There’s also cultural tradition in terms of the fact that a family is carried on through the male line, which may have also contributed to this, but I would bet that if one of these elements had been reversed (either girls traditionally took care of their parents or families were matrilineal) the choice would have still landed on the side of who takes care of the elderly parents.

However, the gender preference has had several side effects. One is obviously the gender imbalance: there are more men than women in China, which means more limited potential partners for heterosexual men. This has resulted, in extreme cases, in trafficking of women both from China but also neighbouring countries to become brides (as well as prostitutes).

It occurs to me that in a world where women are considered autonomous humans, the solution to this conundrum would be for men to actually make themselves attractive to a mate by having something to offer her personality-wise or even in a pure economic sense, therefore giving the woman some power in the relationship; but in this world (and by this world I mean most of the globe, not just China), where women are often seen as commodities, the solution is to steal or buy them.

Feminist tangent aside, another issue that comes from this policy was undercounting of the population. Because each couple had a set quota of one child, if the first child was a girl and the couple wanted to try for a boy but didn’t want to give their daughter up, they may choose not to register her, but this then leads to all kinds of other problems.

If the government doesn’t know these girls exist, they can’t accurately count the number of people they have. This manifested in the 1990 census where the government promised no retroactive penalties for unregistered births in order to get an accurate count and ended up with 13 million more people than expected. This was partially due to statistical flaws in projections, but a large part of it was attributable to girls whose births had never been recorded. (p. 234) This then presents another issue for said girls, as in order to go to school, get a job, finding housing or access state benefits in China (as in many countries) one needs some official record of identity, usually starting with a registration of birth.

In sum, we go from the problem of a large population and the need to reduce the rate of growth to a seemingly logical solution of limiting births. But the reality of social welfare where potential parents may not have other options in terms of support in old age other than their sons leads to a lack of women, which leads to trafficking of women, as well as millions of unregistered women, and, more recently, to pressures on women born in the one-child generations to marry (both from the government and their families) due to the shortage.

So we went from economic and environmental issue of overpopulation to bleak social reality for women in China while barely touching on enforcement methods of the policy (which is a whole other set of problems). This is by no means a full circle overview of the effects of this policy on China either during its enforcement or later, but I thought it was a good illustration of the point here that no issue can exist in a vacuum.

The only drawback of this book (and this is the unfortunate reality of almost all books of its nature) is that it may be a bit dated. The third edition, the one I read, was published in 2010, and obviously there have been many significant world events since then, many of which China has been a key participant in, influence on or at the epicentre of. This is not to say that the book is inaccurate or not worth reading, but many of the chapters would probably have been updated were a fourth edition published today.

There may be more recent books that give a more up-to-date view, but one of the interesting things I found while reading this was actually how many of the key themes the author touched on are still relevant in what I’m seeing being written about China in the media today. For example, there is a chapter on ethnic identities, which covers, among others, a brief overview of the history and plight of the Uighurs, who have, of course, recently been the recipients of much international attention given China’s treatment of them in Xinjiang.

Overall, I think this is very well-worth a read, and I would highly recommend.

Leave a comment